Freight is an often overlooked element of executing large construction projects. Freight is rarely a significant a profit center, but when handled improperly, it can destroy profit margin, infuriate your customer, and impose tremendous execution risk. Here’s five ways to avoid ensure that doesn’t happen to you.

1. Know your Incoterms.

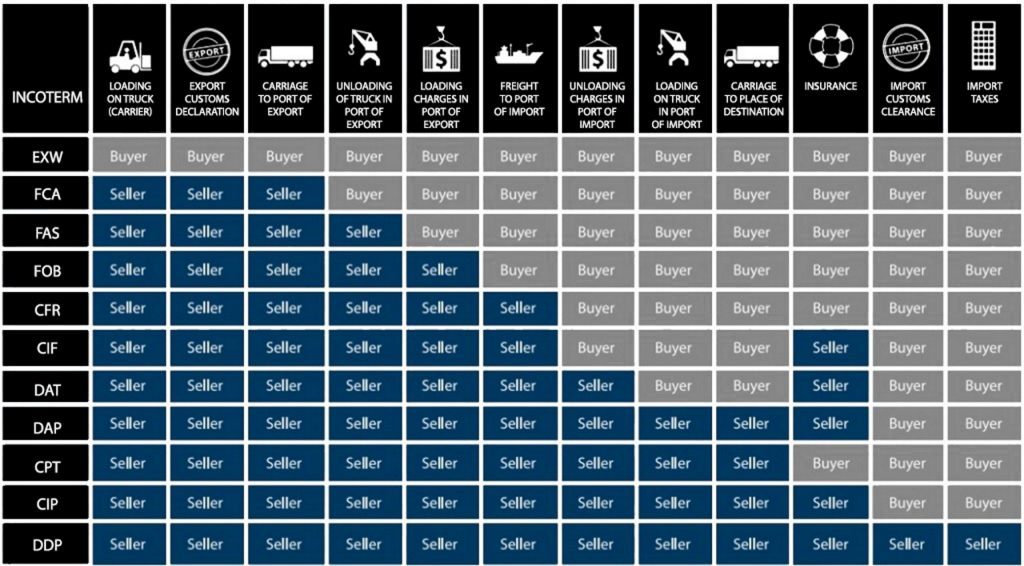

Incoterms define when custody transfer occurs. The example below outlines various terms and what they meant in regards to custody responsibility.

In engineered projects, the vast majority of the time an equipment provider will see terms that are EXW, FCA, or FOB. In layman’s terms, these three terms can be thought of as follows:

- EXW – Ex Works – The equipment supplier finishes the agreed upon scope of work as well as packing it for transport. The physical loading and transport is the buyer’s responsibility.

- FCA – Free Carrier Alongside – The equipment supplier finishes the scope of work and packs it for transport. The equipment supplier is responsible for physically loading it onto the truck at which point liability passes to the transport company and subsequently the buyer.

- FOB – Free on Board – This term is similar to FCA, but applies to sea travel. If the equipment is build next to the water, then it often simply means the provider is responsible to load it onto a barge. If the equipment is far away from the water, it means the equipment provider is also responsible for loading it on the vehicle that transports it to the water. Be careful of the improper use of this term. FOB should always be associated with a port of shipment. For instance, FOB Ingleside, TX is an appropriate term. FOB Lubbock, TX is nonsensical and requires further definition.

Delivered at Terminal (DAT) and Delivered at Place (DAP) are used more rarely and applicable for international shipments where the buyer does not wish to take custody until delivery is made at a port or the buyer’s facility. DAT and DAP terms can pose additional risk to the seller as an equipment provider’s staff may be unfamiliar with customs compliance. Another common phrasing on contracts is not an Incoterm at all, but rather “pre-pay and add”. This means the equipment supplier is in charge of arranging all transport and will mark up the ensuing bill by a set percentage.

Read Also: What are the most popular slots?

2. Never quote a firm freight cost.

Are you an equipment supplier or a slots player? You might as well be the latter if you are trying to quote a firm freight cost on a unit that ships months from now. Things that will probably change between project kickoff and final shipment: the equipment weight, the equipment size, the price of gas, the client bid manager, etc, etc.

Purchase orders should explicitly state any freight estimate is in fact an estimate and will be changed once actual cost is incurred. This is true whether a purchase order was issued against the freight estimate or not. An appropriate freight cost should be assessed when more information is available.

3. Get permits way early.

One of my worst professional experiences was shipping an oversized vessel to Michigan. It was stuck at the border awaiting entry for four days before the permitting went through. I failed to get the right permits because I didn’t properly project how high the finished vessel would set on the truck.

The best way to avoid this problem is have a dependable, trusted freight professional who understands logistical nuances. Talk to them about the project far in advance. Plot the route and plan the permits as soon as practical. Permits will vary from state to state. Generally speaking, shipping to Northern states where bridges tend to be shorter is more challenging for oversized shipments.

(Courtesy GTI Group)

4. Quantify component freight costs

Freight to the end customer is an obvious charge to which attention is commonly paid. What isn’t commonly accounted for are the seemingly small charges when equipment is moved intercompany or to sub vendors during the fabrication process. An example is the cost of shipping a skid to galvanization. Or sending components out for special testing during the fabrication. Extra charges can also sneak in when vendors are not directly involved. A company may account for the total cost of a transmitter as being its landed cost at a central warehouse, not the final fabrication facility for which it is bound.

It is easy to overlook these type of intra-project shipment charges. While overlooking them will not cause dire consequences, margin losses of 1-2% are not uncommon.

5. Gigantic transport equipment doesn’t grow on trees.

Here’s a module that I project managed over seven years ago. Each skid weighs over 200,000 pounds.

Do you think a barge to move that piece of equipment comes along very often? At the time there were only a few worldwide that could move the equipment. Completion schedule had to be planned around the barge availability. Additionally, the effort to move the modules onto the barge was a highly conditioned activity with specialty moving activity.

For best results, be sure your structural engineer is engaged with the land transport company and the barge provider far ahead of the actual move. The logistics team must have a good understanding of the transport requirements and be in contact with well qualified logistics company throughout the move. No matter which INCOterms exist on the purchase order, a logistic company can deliver real value by advising on transport considerations throughout the project’s life.